Evergreen: ÔÇťFLCLÔÇŁ

As a rule, I dislike movies (or TV series, or books) that are deliberately confusing or obtuse. I guess itÔÇÖs because I donÔÇÖt like feeling stupid. For that reason my choice of FLCL as my third entry in my series of articles on ÔÇťEvergreensÔÇŁ is a bit weird. The 6-part OVA (original video animation) series is impossibly dense and deliberately impenetrable. A lot of it does not make sense upon first, or second viewing, or possibly ever.

And believe me, I tried. I tried to make sense of it and I largely failed, and thatÔÇÖs totally A-OK because in the meanwhile I was treated to big robots spawning from the head of the protagonist, said robots being hit by bass guitars, sexual innuendo, and references to everything from an opening movie for a 1983 Japanese science fiction convention to The Matrix to South Park. And you donÔÇÖt need to understand any of that either, because you can just watch it and be immersed in the lavish visuals, the kinetic animation and the rocking soundtrack. Oh that soundtrack!

What?

FLCL is about a 12-year-old boy, Naota, growing up and struggling with his puberty. His brother has travelled to the United States to play baseball, so Naota is left behind, living with his father and grandfather. (Their mother has presumably passed away years ago.) Naota is a surly guy who despises the stupid adults around him and the town where heÔÇÖs growing up, where nothing ever happens. He even says this in a voice-over after the opening scene. ÔÇťNothing amazing happens here. Everything is ordinary.ÔÇŁ

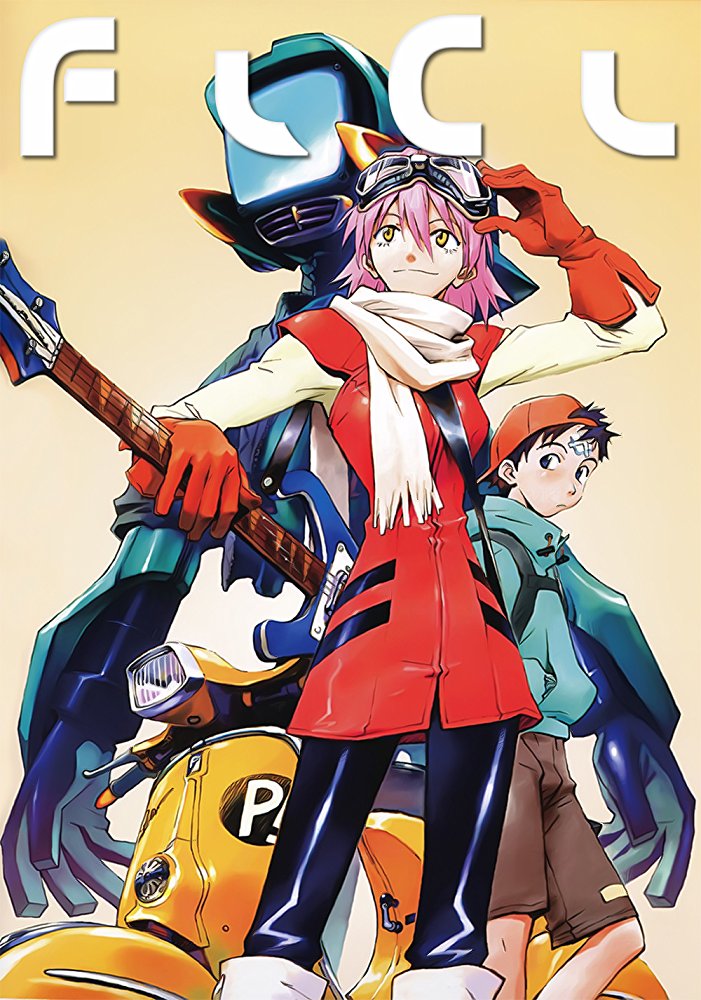

This, of course, is asking the movie gods for trouble. Enter Haruko Haruhara, an almost ideal embodiment of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope. She rides a Vespa and plays a Rickenbacker bass and has pink hair. SheÔÇÖs also an alien and doesnÔÇÖt care about anything but herself and a space pirate sheÔÇÖs in love with — but we donÔÇÖt know that yet. (And much of this will only be explained in the final episode.) In her entrance Haruko first bowls over Naota in her Vespa, then brings him back to life by CPR and then proceeds to hit him on the forehead with her Rickenbacker.

This causes a horn to grow from his forehead. Later, after an emotional talk with the former girlfriend of his brother, the horn erupts and a TV-faced robot and the hand of another robot emerge. They fight and TV-bot wins, but heÔÇÖs beaten in turn by Haruko with her Rickenbacker. And thatÔÇÖs a highly abbreviated summary of the first episode.

Wait, let me put it in another way. Just watch this ÔÇťanime music videoÔÇŁ created from footage of FLCL put expertly to the song ÔÇťSpeed KingÔÇŁ by Deep Purple.

The original is maybe not quite as frantic as this distillation, but itÔÇÖs not far off.

No, seriously, what?

FLCL was written by Y┼Źji Enokido and directed by Kazuya Tsurumaki, both of whom worked on Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995–1996). The series was produced by Gainax and Production I.G, who, yep, both worked on Neon Genesis Evangelion. FLCL was meant to blow off steam for the teams, after the gruelling production of NGE and End of Evangelion (1997). So itÔÇÖs probably not a surprise that FLCL is full-out-crazy. Like, pants-on-your-head running-around-in-the-rain-singing-La-Marseillaise weird. ItÔÇÖs also as energetic as a toddler after drinking two double caff├Ę macchiatoÔÇÖs and eating a bag of M&Ms.

Slightly more surprising maybe is the fact that even though the teams were burnt out from Eva, thereÔÇÖs still a lot of themes from that series in FLCL. While Eva was a deconstruction of the mecha genre (which immense success revitalized the industry), FLCL can be seen as a deconstruction of Evangelion, while happily drinking of the same well. So here we have again the sulky young boy who is forced to grow up and an uncaring father, a missing mother.

Stranger, then, is the fact that FLCL is also a heart-warming rendition of the pains of growing up and the strange time in oneÔÇÖs life that is puberty.

Strangest of all, though, is that FLCL does all of this, has all these layers, packs it in six episodes with a total running time of barely two-and-a-half hours, and succeeds.

LetÔÇÖs rock!

The seriesÔÇÖ music deserves a special mention. The score is written by Shinkichi Mitsumune and while itÔÇÖs probably good, itÔÇÖs not what fans think of when FLCL is mentioned. That honour goes to the music of The Pillows, a Japanese (alternative) rock band. Most anime series had (and have?) some J-Pop song playing over the opening and closing credits. Not so FLCL! Tsurumaki wanted to ÔÇťbreak the rulesÔÇŁ with his anime so he instead chose to feature contemporary rock music. They licensed the three most recent albums by The Pillows (Little Busters, Runners High and Happy Bivouac) and used those.

Recently I re-watched the series in preparation for this article and I noticed some additional things. First, the thing is filled to the brim with The PillowsÔÇÖ songs. Even during scenes where thereÔÇÖs little action happening, just some characters having a conversation, the fuzzy guitars of the songs would be rocking along. Secondly, itÔÇÖs astounding how well-synchronized the scenes are to the music. Apparently this was done by choosing the song first and then timing the animation to it.

I honestly donÔÇÖt know how good the music is, in itself. In my mind itÔÇÖs been fused with the experience of watching FLCL. Neither can I imagine watching FLCL without the riveting songs from The Pillows. I wouldnÔÇÖt want to live in such a world.

Most of the songs have lyrics in Japanese, although some of them have some phrases in English laced through them. The English phrases donÔÇÖt exactly make sense, and looking at translations of the Japanese, they donÔÇÖt make sense either. That doesnÔÇÖt matter because thereÔÇÖs something immensely satisfying about humming along to the songs and singing things like:

GRUNGE no HAMSTER otona bite

REVENGE no LOBSTER hiki tsurete

SNIPER

fuchi totta sono sekai ni

nani ga mieru tte iu n da

nerau mae ni sawaritai na

Ride on Shooting Star

kimi o sagashite kindansh├┤j├┤ ch├╗

uso o tsuita.

There are three soundtrack albums, conveniently named No. 1: Addict, No. 2: King of Pirates and No. 3. Number 1 and 2 contain music and songs (mostly instrumental versions) from the first and second half of the series, respectively. Number 3 is a collection of the songs by The Pillows, now in the original versions.

Further viewing

Well, more a ÔÇťRecommended viewing before watching FLCLÔÇŁ this time around. The elephant in the room here is obviously Neon Genesis Evangelion. Its production was plagued with issues, like budget cuts, massive changes in the scripts, looming deadlines, etc. Director Hideaki Anno based the plot on his four years of depression following his previous work, and reflects his interest in psychology. The original ending was a big let-down. ThereÔÇÖs mood whiplash from teen high-school romance to deep existential dread, father-son relationship issues and esotericism. The enormous number of themes in the series sometimes result in a confusing mess, a train-wreck of ambition, or a glorious deconstruction of mecha anime, or all of that at the same time — depending on who you talk to. It spawned a devoted fan-base, a mega-franchise, an alternative-ending movie, and a four-feature-movie-long reboot/remake. It rewrote the book on what an anime could be.

IÔÇÖd just start at the original TV-series, then maybe watch The End of Evangelion, and if youÔÇÖre still interested, move on to the reboot.

The creators of FLCL and the rest of Gainax created a lot of other stuff, none of which I actually watched completely. I tried to watch Tengen toppa gurren lagann but my interest fizzled after 10 or so episodes, and I never finished it. SoÔÇŽ thatÔÇÖs about it.

Instead I can offer some advice on how you could approach FLCL. Take this with a heavy load of salt, as thereÔÇÖs no One True Way for such a dense series. First off, just watch it. Yep, just go in blind and let FLCLÔÇÖs madness engulf you. DonÔÇÖt try to make sense of it, just let it happen.

Then, after some time to let it sink in, you can opt for another viewing, to see if it makes more sense the second time around. If youÔÇÖre more impatient, you can also read these articles on The A.V. Club which point out some of the things you might miss otherwise, and help with understanding the themes.

After this guided course you might be interested in the directorÔÇÖs thoughts so re-watch it again with Kazuya TsurumakiÔÇÖs commentary track, where youÔÇÖll find out that not all of the little details are as meaningful as some people think.

Alternately, you can watch this video by Kristian ÔÇťKaptainKristianÔÇŁ Williams who brings up a good point: ÔÇťIf FLCL seems to you like an incoherent mess, just remember how you saw the world when you were twelve.ÔÇŁ

Last year, Toonami announced two new seasons for FLCL. IÔÇÖm not sure that the series needs more episodes, but a lot of the original crew seem to be involved —among them the original director, Kazuya Tsurumaki— so I am cautiously optimistic. After all, FLCL is my kind of crazy.