Evergreen: “Kingdom of Heaven”

Last updated on 30 December 2020.

After the 3000+ word examinations of The Godfather and Firefly I wanted to do a shorter discussion about Sir Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven (2005). Then I got sucked into the extra features on my 4-disc DVD set of the movie, so the odds of this being a breezy article are slim.

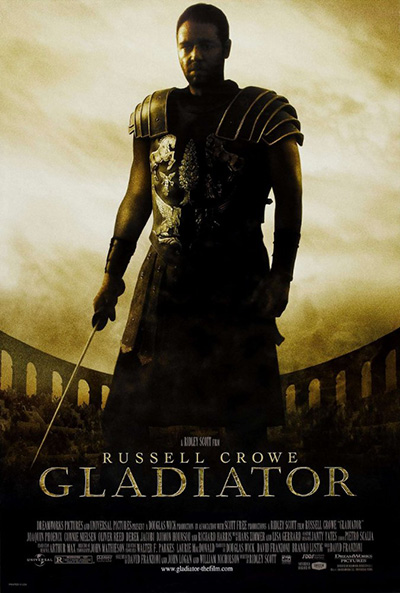

To be fair, those odds were always against me. Ridley Scott has made some of my favourite movies, among them Blade Runner (1982) and Gladiator (2000). I’ll cover the former in a future article, and the latter was in the running for its own article. It won’t get that, but I will often refer to this movie while discussing Kingdom of Heaven as there are many parallels.

Moreover, Kingdom is a long movie, with many characters, many plot threads and some interesting themes. Discussing it all will take some time. There’s also the issue of historical accuracy that needs to be addressed, and of course I’ll talk about the musical score. So much to write about, so let’s get into it.

This article contains many, many SPOILERS for Kingdom of Heaven.

Before we start proper, I have to mention quickly that there are two vastly different versions of the movie out there: the Theatrical Version and the Director’s Cut. I will discuss the latter, except where noted. We’ll get back to the differences and why I prefer the Director’s Cut.

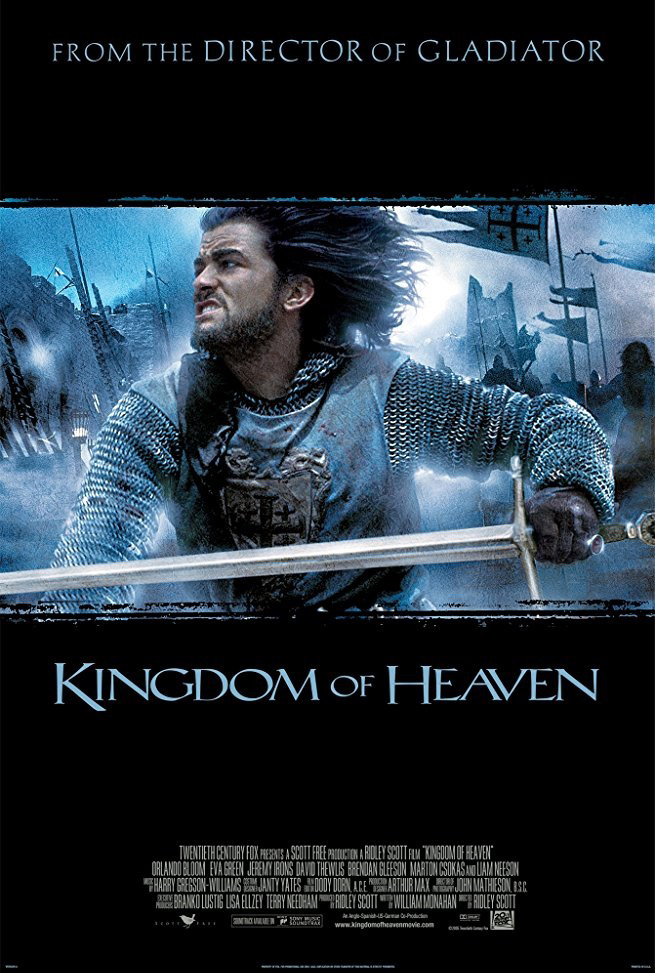

The short summary of Kingdom of Heaven is that it’s a 2005 historical epic set in 1184, shortly before the Third Crusade. The movie tells a highly fictionalised version of the life of Balian of Ibelin (played by Orlando Bloom). He travels to the holy city of Jerusalem to find salvation for his wife and himself. Here he gets swept up in the politics of the time and place.

The Lay of the Land

As I mentioned in the introduction, Ridley Scott also directed Gladiator, the 2000 historical epic starring Russell Crowe. It was a great success, both critically and commercially. It’s grand and colourful and baroque and bombastic (music by Hans Zimmer!). It draws upon Scott’s strengths as a filmmaker, with stylised shots, lavish production design, characters painted in broad strokes upon a semi-historical canvas.

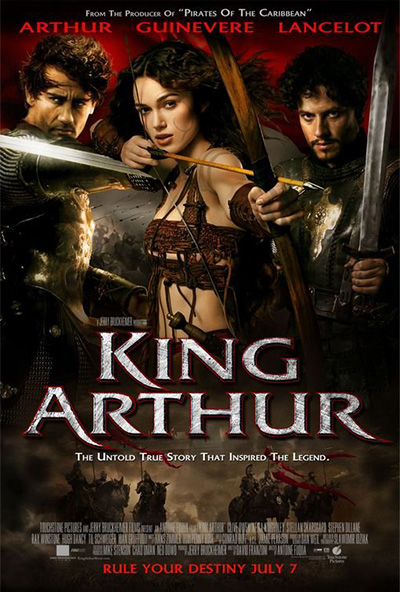

It would cast immense shadows in Hollywood and afterwards, loads more epics were released, including (semi-)historical ones like Troy (2004), King Arthur (2004) and Alexander (2004), and fantastical ones like the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Some of these were good, some of them… less so. A lot of them bore the trappings of Gladiator (bombastic music, sprawling stories, lavish costumes, a lot of colour grading and enormous battle scenes) but not all of them had an interesting story to tell or the cast to support it.

In the meanwhile Scott was trying to get Tripoli off the ground, another historical film (about the First Barbary War) with a script by William Monahan. It was in an advanced state of pre-production but eventually was cancelled. A lot of the crew kept together and the production pivoted to what would become Kingdom of Heaven. In this crew we find many people who previously worked with Scott on Gladiator or other movies: producers Branko Lustig and Terry Needham, cinematographer John Mathieson, set designer Arthur Max, costume designer Janty Yates, set decorator Sonja Klaus.

The Hero’s Journey

To expand on the summary I gave some paragraphs up, let’s dive deeper into the story and its many characters.

Balian starts the movie as a blacksmith, in a town in France. He’s grieving because his wife committed suicide after his young child died, damning herself to hell. Crusaders visit the town: Godfrey, Baron of Ibelin (Liam Neeson), looking for his bastard son in the town where his brother is the lord. He asks Balian for forgiveness, as he more-or-less forced himself upon Balian’s mother, never acknowledged him and certainly never cared for him. Balian takes this in stride (whether he’s profoundly depressed or just stoic is hard to gauge) but he declines Godfrey’s offer to travel with him to Jerusalem and be under his keep.

This is a classic Hero’s Journey setup, a Call to Adventure, or in literary terms, the Inciting Incident. Interestingly enough, Balian declines the Call… or does he?

Because there’s also a priest (Michael Sheen) who’s Balian’s brother. He stole the silver crucifix from the woman’s corpse, and ordered the wife’s head to be cut off, and then lied about it. He’s very eager to see Balian depart and wants him to go with Godfrey. (Why?) He’s also stupid because he actually wears the crucifix while needlessly taunting Balian. “I put it delicately… She was a suicide. She is in hell. Though what she does there without a head…” [shit-eating grin]

Seriously, there’s so many thing wrong with this priest character, it annoys me every time.

The actual Inciting Incident is that Balian then kills his brother and lets his smithy burn down. (And who could blame him!) He flees, catches up with Godfrey and his men and joins them. “Is it true that in Jerusalem I can erase my sins and those of my wife?” This, then, is Balian’s motivation.

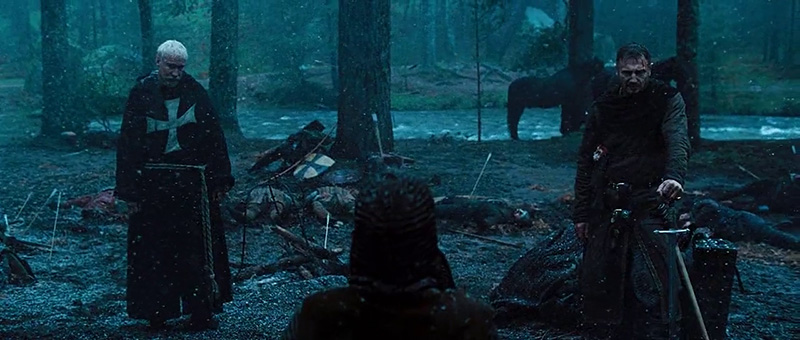

Balian quickly receives a training montage about sword-fighting, before the whole group is surrounded by Godfrey’s nephew and his men who wants to arrest Balian. Weirdly enough, Godfrey decides to fight them over Balian. Poor Liam Neeson, he didn’t realise he’d signed up for the Sean Bean role! While the hardened crusaders defeat the Franks even from a disadvantageous position, Godfrey’s struck by an arrow and will die on the road to Messina. But not before he can impart his dream to his bastard son:

“Do you know what lies in the Holy Land? … A new world. A man who, in France, had not a house is, in the Holy Land, the master of a city. He who was the master of a city, begs in the gutter. There, at the end of the world you are not what you were born but what you have it in yourself to be. (...) A better world than has ever been seen. A kingdom of conscience. A kingdom of heaven. There is peace between Christian and Muslim. We live together. Or, between Salah ad-Din and the king, we try.”

I’m not a scholar but this to me seems like a very modern (or even postmodern) notion for a medieval person to entertain. It won’t be the last of these 21st-century attitudes that our heroes hold. Actually, it’s not even the first: in the opening scenes we see an engraving in Balian’s smithy that says (in Latin): “What man is a man who does not make the world better?” That seems a long ways away from a medieval man who believes in predestination.

All this takes about 35 minutes to unfold, and Balian has barely arrived in Messina. He continues his voyage by boat, which is promptly shipwrecked. All alone, separated from his father’s men, he washes ashore in a desert, where he defeats (with the help of his training montage) two Saracens: a knight and his servant. He lets the servant live and uses him as a guide to reach Jerusalem. There he lets the Saracen go, and the man tells him: “Your quality will be known among your enemies before ever you meet them, my friend.” There are traces of Gladiator in this line, which told us “what we do in life echoes in eternity”. To be honest, I absolutely adore lines like these. Nobody would ever say these words in reality, but in movies like these they make perfect sense and are delivered with a gravitas that makes my toes curl.

In a way, the movie we’ve seen so far is an adventure movie. The hero is wrenched out of his familiar surroundings and goes on to travel across the lands, where he meets both allies and enemies. Over the next few scenes, the focus of the movie will change.

We’ve arrived in Jerusalem, after all, and in the movie it is a foreign but luscious place. The palette has shifted from the drab, dark hues from Europe to the bright and warm colours of the Orient. Jerusalem and its people are amazing to see: it’s a busy city, the navel of the world, full of motion and painted in rich, deep colours. According to the bonus features Ridley and his set designers were influenced by a Romantic view of the East, and it shows. As production designer Arthur Max puts it, it’s “based on Romantic impression and imagination”. The movie doesn’t necessarily try to give a realistic presentation of the East: it’s inspired by a 19th century impression of the 12th century. During pre-production they visited the Salles des Croisades ("Hall of Crusades"): a set of rooms in the Palace of Versailles full of paintings about the Crusades.

Balian doesn’t find peace of mind, although the finds the men of his late father. This includes the Hospitaller (David Thewlis), who tells Balian and the audience what one of the messages of the movie is:

Balian, being emo: “God does not speak to me. Not even on the hill where Christ died. I am outside God’s grace.”

The Hospitaller, wryly: “I have not heard that.”

“At any rate, it seems I have lost my religion.”

“I put no stock in religion. By the word ‘religion’ I’ve seen the lunacy of fanatics of every denomination be called the will of God. I’ve seen too much religion in the eyes of too many murderers. Holiness is in right action and courage on behalf of those who cannot defend themselves. And goodness, what God desires, is here [points to Balian’s head] and here [points to his heart].”

He’s also visited by Sibylla, Princess of Jerusalem (Eva Green), who seemingly mistakes him for a servant. Sibylla is presented here as an aloof, exotic beauty and frankly, she’s stunning. She’s the first female character we meet, apart from flashbacks to Balian’s wife. Come to think of it, she’s pretty much the only female character in the movie and certainly the only one who has agency. Which, as I now realise, closely mirrors Gladiator, where the only woman in the entire movie was Connie Nielsen’s Lucilla.

The Hospitaller brings us to Tiberias, the Marshal of Jerusalem (gravelly-voiced Jeremy Irons — you probably know him as Scar from The Lion King). In the meanwhile we’re given a whirlwind tour of the political situation, and the movie shifts to a courtly intrigue. With Salah ad-Din, King of the Saracens on one side, fanatics like the zealous Knights Templar and their leader Reynald de Chatillon on the other side, Jerusalem is a powder keg waiting to blow. Tiberias tries to keep the peace as the King of Jerusalem ordered him, and Salah ad-Din tries as well, but fanatics on either side try to provoke a war, saying that “God wills it”. He’s also introduced to Baldwin IV, the Leper King of Jerusalem (Edward Norton), who charges him to protect the pilgrim road: “Protect the helpless.”

He also states one of the main themes of the movie:

“When I was sixteen I won a great victory. I felt in that moment I would live to be a hundred. Now I know I shall not see thirty. None of us know our end really… Or what hand will guide us there. A king may move a man. A father may claim a son. That man can also move himself. And only then does that man truly begin his own game.

“Remember, how so ever you are played, or by whom, your soul is in your keeping alone. Even though those who presume to play you be kings or men of power. When you stand before God, you cannot say ‘but I was told by others to do thus’ or that ‘virtue was not convenient at the time.’ This will not suffice.”

Balian then goes to Ibelin and the estate of his late father, a dusty place but paradise to him. Fortunately, Balian is an engineer and teaches his people to dig for wells. Apparently they hadn’t figured this out yet. A problematic scene (the Western man teaching the “natives”), but it reinforces that Balian is a man of the people, who tries to make the world a better place.

He’s visited by Sibylla again, who’s smitten with him and his earthly, forthright ways (or so it seems) — and who deftly seduces him. It’s fun to see the contrast between the coarse, grumpy Balian and the fey-like, sensuous Sibylla. I’m not sure how much of Balian’s sullenness is due to stage directions and how much is Bloom’s limited range, but it makes Eva Green’s performance sparkle all the more.

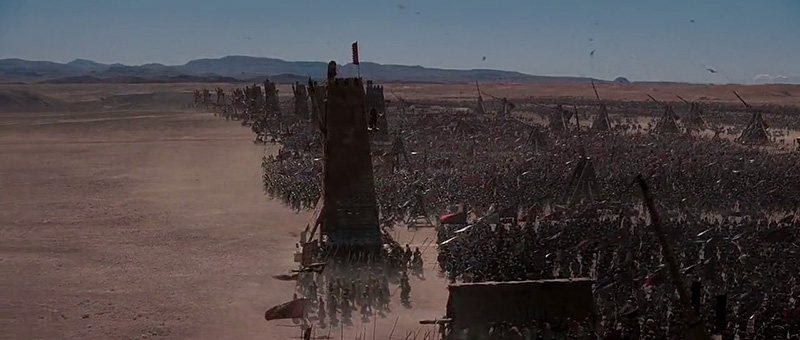

While our two protagonists are having their affair, the Templars are massacring a caravan of Saracens. The movie reminds us that we signed up for a historical epic, not a rom-com. Thus provoked, Salah ad-Din marches for Kerak, stronghold of Reynald, and Baldwin feels forced to respond. Balian is sent for to protect the people outside of the walls, and he does so by stalling a much larger force of Saracen cavalry. This, then, is what we signed up for: mass warfare with two forces charging at each other, thundering hooves and music, the clash, chaos and bloodshed, slow-motion shots of people dying in brutal fashion, ethereal choirs in counterpoint. Scott and his team are in their element and it’s a sight to behold.

It’s over quickly, though, Balian’s meagre force no match for the Saracens, and the survivors are taken captive. He meets the “servant” he met in the desert again, who turns out to be a high-ranking knight in Salah ad-Din’s army. He echoes his own words: “Your quality will be known among your enemies before ever you meet them, my friend.” He lets Balian enter Kerak, “but you will die there. My master is here.”

However, the stalling was successful and the Crusader’s army has arrived. Baldwin swiftly negotiates a truce: “Reynald de Châtillon will be punished. I swear it. Withdraw, or we will all die here.”

Reynald is punished, war is avoided, but the march has worsened Baldwin’s condition and he’s dying. To counter Guy’s faction, he offers Balian the command of his armies and his sister’s hand. The price: Guy would have been executed, along with any of his knights that do not swear allegiance to Balian.

I’ve given Orlando Bloom some flak for his acting, but to be fair to him, he isn’t given a lot to work with. His character’s emotional journey is not so much an arc as a straight line with a small bump around the time he gets seduced by Sibylla. He arrives in the story as a fundamentally good man and then has his beliefs confirmed and reaffirmed by his father and his king. Despite all he sees and what it costs him, he sticks to those convictions. Balian is so morally upright that he doesn’t even give in when he’s offered the kingdom and the hand of the woman he loves. As king, he would be in a much better position to help the people, avoid war, protect the peace… but he declines, even when Sibylla urges him: “There’ll be a day… when you will wish you had done a little evil, to do a greater good.”

As if it’s not bad enough, the audience notices that Sibylla’s son, the heir to the throne, is a leper, just like his uncle. In a flurry of short scenes, Baldwin dies, and Sibylla, desperate, makes a deal with Guy. She will support him and become his wife (not just in name), in return of his knights, to support her son. The son’s crowned king, but his leprosy is noticed by Sibylla and others shortly afterwards. Sibylla can’t stand the thought of the suffering in her son’s future: “Jerusalem is dead, Tiberias. No kingdom is worth my son alive in hell. I will go to hell instead.” In a gut-wrenching scene she takes her son’s life by pouring a poison in his ear, after having sung him to sleep with a French lullaby.

Sibylla is crowned queen, but has to take Guy as king. He quickly pardons Reynald and urges him to “give me a war.” The Templar does so with gusto by murdering Salah ad-Din’s sister. The Templars finally have their war and march to war. Balian, Tiberias and their forces remain behind because as they disagree with Guy’s acts but also his plans: he wants to march through the desert, for days, without access to water.

The overzealous Templars think that “God wills it.” The Battle of Hattin ensues, and the Crusader army is annihilated. In a smart move, Ridley does not show the battle itself, but only the aftermath. Reynald is beheaded by Salah ad-Din, but Guy is given mercy. We’ll see him later being paraded about on a donkey when the Muslim army arrives at Jerusalem’s gates.

Now the movie shifts gears again as we see the siege of Jerusalem. Our hero Balian leads the defense against an overwhelmingly large force. Depending on your tastes, this last act in the very long movie is either the pay-off of all the politics and romance, or a boring let-down after the same. When I first saw the movie I was probably more leaning towards the former, and now more towards the latter. It’s not that it’s bad movie-making: Ridley Scott and his team create a tense siege that feels epic while also focussing enough on smaller stories that play out in the grander conflict. A few years before The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002) set a new standard for sieges in movies in its Battle of Helm’s Deep. I don’t think Scott’s version of the battle for Jerusalem quite hits that mark, but it’s certainly one of the most impressive and well-directed pieces of warfare. Big charges, thunderous music, rousing speeches, move and counter-move: it’s all here, in splendid shots and cinematography. There’s also a twist to the default recipe, in that Balian doesn’t fight to win: he only fights to bloody the enemy enough that they offer terms. He wants to make taking the city cost enough Muslim lives that Salah ad-Din doesn’t want to spill more blood, and lets the civilians live. So Balian surrenders the city, but it’s a victory nonetheless.

This is a perfect spot to wrap up the movie, but weirdly Scott adds some extra scenes.

Particularly puzzling are two scenes related to Guy de Lusignan and his wife Sibylla.

Guy survived his captivity and was delivered to the forces of Jerusalem. He somehow thinks it’s a good idea to attack Balian one-on-one, who defeats him (as he’s been doing the entire movie, in one way or another) but lets him live with the message. “When you rise again, if you rise… rise a knight.”

In the last scene, we see Balian return back to his home village. Here he meets a fresh crop of Crusaders, on their way to Jerusalem, led by Richard the Lionheart. They’re looking for “Balian, who was defender of Jerusalem.” He pretends he’s just the blacksmith, and the crusaders ride on. In the next shots, Sibylla is with him, and then they ride on, together, ostensibly towards Jerusalem.

The former seems to reinforce that Guy never learns, and that Balian is still capable of turning the other cheek. In other words, we learn little new, so why add this scene. The last scene is especially puzzling to me. That Sibylla and Balian hook up seemed a given, but why would they return to the war? What am I missing here?

A Movie under Siege

At this point you might be wondering why I’m writing such a critical article about this movie that I supposedly love. I guess that’s a fair question. The main answer is that if I sound too negative, it’s mostly because my writing might not be up to the task (yet) of writing a balanced critique of the movie.

Secondly, writing a critique was actually not my intention. I just wanted to write an article about a movie that I like, recommend it to others for they might have missed it, and along the way figure out why I like it. While writing this kind of “Evergreen” review of Kingdom of Heaven, it got away from me. There’s just so much to say about a movie of this length and ambition.

Thirdly: in the past few “Evergreens” I often started writing about the plot, and then I let that fizzle out while I jumped onto other subjects. I wanted to know where I would end up if I just stayed with it.

Besides, a lot of the things I mention are by no means dealbreakers, nor are they things that jump out upon first viewing. Indeed, it’s entirely possible to watch the movie without ever noticing the beauty marks, such as they are.

Last but not least, I think it’s entirely possible to be critical of a work of art and still be very fond of it.

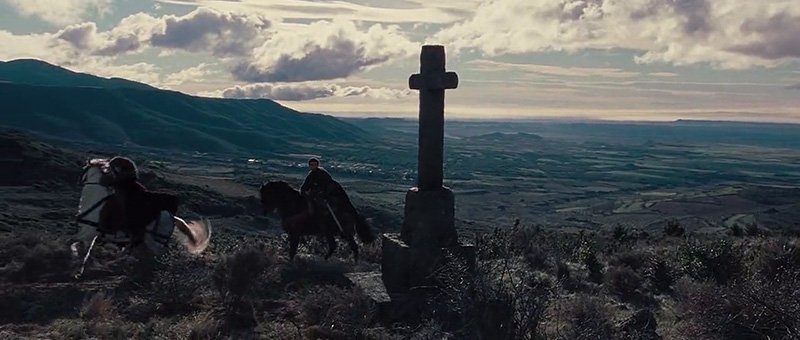

Still, to avoid any confusion, let me list some things that like about the movie! First of all, the cinematography is stunning. Scott has a sumptuous visual style (appropriate for somebody who cut his teeth on commercials) and he went all-in on this movie. He is supported by his crew, his cinematographer John Mathieson leading the charge. As you can see from the screencaps above, the man knows how to frame a shot in such a way that it could be a painting. Using the light in dramatic ways, Scott and Mathieson achieve thrilling chiaroscuro.

Obviously, it helps that the movie was shot on location in Spain and Morocco. Various actual landscapes and old buildings stood in for France, the Holy Land and Jerusalem, such as Huesca, Aragon and Alcázar of Sevilla in Spain. They also built an enormous set in the desert near Ouarzazate, Morocco.

Then, of course, there’s the cast. It’s an embarrassment of riches. Poor Orlando Bloom could not help but be overshadowed by co-stars as the leading roles went to the likes of Eva Green, Edward Norton and Liam Neeson — perversely, Norton acts behind a mask and Neeson dies in the first act. But the supporting actors are all very good as well: Michael Sheen (Frost/Nixon, The Queen), David Thewlis and Brendan Gleeson (Remus Lupin and ‘Mad-Eye’ Moody in the Harry Potter movies), Jeremy Irons… it’s a veritable who’s-who of (British) acting talent. And if you pay attention, you could recognise Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as the village sheriff. You probably know him as Jaime Lannister from Game of Thrones.

I’ve already touched upon the quality of the dialogue and frequently quoted from it. It might not be Shakespeare, but there’s a good deal of solemn speeches that I enjoy immensely.

The Message

There’s a lot to unpack about this movie as there are many themes and messages. Some of them only hinted at, hidden in the subtext, while others are less subtle. So let’s talk about the elephant in the room.

The closing title card states:

“The King, Richard the Lionheart, went on to the Holy Land and crusaded for three years. His struggle to regain Jerusalem ended in an uneasy truce with Saladin. Nearly a thousand years later, peace in the Kingdom of Heaven remains elusive.”

The movie was released in 2005: relatively shortly after 9/11. As such, it can’t be seen separately from the zeitgeist, one of warmongering and intolerance. Scott did something unusual, and dare I say it, brave: he put a strong message of (religious) tolerance in his blockbuster movie.

It’s certainly not a subtle message, and it’s delivered with all the grace of a rock being catapulted into a city wall. Both sides have their own version of zealots, thirsty for blood and war. Especially the Templars are depicted as mustache-twirling villains, with Reynald de Châtillon being a crude, bloodthirsty loudmouth who gladly pillages, kills and rapes. Guy is not just somebody who desperately wants to be king: he’s a stuck-up, arrogant prick who shags a servant and perpetually looks down on the lesser-born Balian.

The fanatics on both sides are absolutely sure that they know what God wants and that it is war over the Holy Places. Both sides also have kings that try to avoid peace, but are unable to stem the tide. If not for the religious fervour of the outliers, the world would be a better place.

Then again, as the message was spoken in those times to an American audience, it’s probably best that it wasn’t subtle. As the late Roger Ebert put it:

“The second thing is that Scott is a brave man to release a movie at this time about the wars between Christians and Muslims for control of Jerusalem. Few people will be capable of looking at Kingdom of Heaven objectively. I have been invited by both Muslims and Christians to view the movie with them so they can point out its shortcomings. When you’ve made both sides angry, you may have done something right.”

Music from Heaven

Kingdom of Heaven’s soundtrack was composed and conducted by Harry Gregson-Williams. He worked previously with Ridley’s brother, the late Tony Scott (Enemy of the State, Man on Fire), but also collaborated on various works with Hans Zimmer. Mr. Zimmer was of course the composer on Gladiator and his influence on the epic-movie-soundtrack business would be enormous. It’s easy to see why: he has a way of mixing the grandiose and bombastic while weaving in subtle, fragile melodies between all the thunder.

In a way, Gregson-Williams’ work on Kingdom of Heaven is cut from the same cloth, as there are a lot of stirring battle anthems. At the same time, I feel that there is a lot more subtle themes. Part of the lighter touch are the medieval and Eastern instruments, that add a certain levity and exotic textures.

I’m rapidly approaching the end of my vocabulary here as I’m no expert in (classical) music, so allow me to quote from James Christopher Monger’s review for AllMusic:

“Williams approaches the era with a far more delicate touch than Zimmer, utilizing period and regional instrumentation, as well as lush choral arrangements to accentuate the film’s romance and religiosity. While there are plenty of instances where thunderous percussion and sweeping brass paint gallant images of galloping horses and tattered flags, there are more moments that effectively portray the bloody fields and pious ruminations of war.”

I’m particularly fond of the choirs, and the fragile themes such as in “Ibelin”:

More about its musical themes can be found in this excellent YouTube playlist.

Kingdom’s soundtrack quickly found its place into my record selection, and I listen to it often on its own, not watching the movie. It finds companionship there with James Horner’s soundtrack for Braveheart, Zimmer’s work for Gladiator, King Arthur, Nolan’s Batman trilogy and Inception; and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s work for The Social Network.

A Tale of Two Cities

As noted in the introduction, there are two versions of Kingdom of Heaven: the Theatrical Version and the Director’s Cut. The first was released to the greater public and runs 144 minutes. Later that year the Director’s Cut was published to a limited number of theaters. (I don’t think it was ever released to theaters in the Netherlands, though.) This version, weighing in at a handsome 190 minutes, is the one you should watch.

At almost two-and-a-half hours, one would think the Theatrical Version would have enough time to tell the story, and that there’s no need to add another 45 minutes. Of course, Ridley Scott is not known for his restraint. There’s no grandiose gesture, no melodramatic scene nor gorgeous scenery porn that he hasn’t indulged in. In this case I can see where he’s coming from. The Director’s Cut vastly improves upon the characterisation and flow of the original. There are many differences between the versions, and if you’d really like to read a side-by-side comparison, you can. The two biggest differences are as follows.

Firstly, in the Theatrical version, the introductory scenes are much shorter. We learn a lot less about Balian: about his history, his relationship with the priest, and why he leaves his hometown to go crusading. This makes the entire movie shaky, as the protagonist’s motivations are what propel the story forward. It also leaves out small but important tidbits like the fact that Balian has fought in wars before, and was a siege engineer. Even with that knowledge his propulsion into a capable commander of armies and defender of Jerusalem feels fantastical, but without it his arc feels downright ridiculous.

Furthermore, in the Theatrical Version Sibylla does not have a son, let alone a leper son, who would succeed her brother. Tellingly, her conversation with her husband Guy de Lusignan was changed from “If I have your knights, you have your wife” (Theatrical Version) to “If my son has your knights, you have your wife” (Director’s Cut). This fundamentally changes Sibylla’s motivations. As Daniel Netzel notes in the essay below: “It wasn’t a selfish act of self-preservation, but a sacrifice made from a mother’s love.”

In fact, it’s a bit wrong to think of the Theatrical Version as “the original”. Even while shooting, Ridley was always ambiguous about which version (“with boy” or “without boy”) he’d create. He kept delaying the decision and shot the movie for both versions. Even when shooting had finished he hadn’t decided yet. According to IMDb, “[t]o create both the theatrical cut, and the Director’s Cut, Editor Dody Dorn worked for fifteen months straight. The average film takes, at most, four or five months to edit.”

She notes in the additional features on the DVDs: “To me they feel like two different films. One film seems like an action-adventure, sword-and-sandal film, and the other film seems to me like a sophisticated historical epic.” I can’t disagree with her, and it’s easy to see why the studios pushed for the Theatrical Version to be created.

Historical Accuracy

Every “historical” movie will be judged to a certain degree on how close to history it hews. Kingdom might have had more scrutiny because of its subject matter and themes. This is tackled during one of the featurettes on the Director’s Cut DVD set, “Creative Accuracy: The Scholars Speak”. In it, various experts give their views on the movie. Of course, they’re all on the side of Scott and allow great diversions from history in favour of a more compelling story and movie.

Here are some quotes from the feature:

“One thing that I would say is a little bit different in the film than what we might expect from the mentality of a medieval person in reality is that Baldwin, and also Balian and many of the other characters, are depicted as having a sort of philosophical commitment to religious pluralism.”

— Dr. Nancy Caciola, PhD., University of California, San Diego

“We do know historically that there was a general, Balian of Ibelin, who was involved in these events and who surrendered the city of Jerusalem. Again though, the scriptwriters have sort of taken some artistic license here.”

— Dr. Nancy Caciola, PhD., University of California, San Diego

“It is true to say that nobody in the Middle Ages would’ve talked about religious tolerance, an ecumenical attitude, an openness to all faiths, it would never have occurred to them.”

— Dr. Donald Spoto, writer / theologian

It’s saying a lot that the villains in the piece, the Knights Templar, are probably a more correct representation of then-contemporary ideas.

Meanwhile, Ridley Scott firmly pitches his tent with the brief statement: “I am a movie maker, I’m not a documentarian.” Anyone who has seen Gladiator or any other movie by Ridley Scott would know what to expect in this regard. Remember that 1492: Conquest of Paradise (1992) is also by him.

Further Viewing

If you’re into historical epics or sword-and-sandals movies, there’s of course plenty to watch. I’d start off with Braveheart (1995), Mel Gibson’s project about William Wallace, the Scotsman who lead a rebellion against the English in the First War of Scottish Independence. The battle scenes are contrasted with political intrigue and some romance (the lovely Sophie Marceau), as many of these stories tend to. I’ve written elsewhere about my love for its soundtrack.

After this appetiser you can move on to Gladiator (2000), the one that kicked off a hausse in historical epics, for better and for worse. Its story is actually rather straightforward, but the cast is very good: Russell Crowe (“who combines an underdog role with the biomechanics of a bulldozer”), Joaquin Phoenix, Oliver Reed, Richard Harris. Its soundtrack (Zimmer working with Lisa Gerrard) is all kinds of amazing, and it also let Scott exercise his stylistic muscles and love of great set design, gearing up for Tripoli and eventually Kingdom.

Round out your three-parter with King Arthur (2004), an outsider in the genre. Yes, it’s about the Arthurian legend, but in director Antoine Fuqua’s version Arthur is a Roman officer (Clive Owen), his Knights of the Round Table are his fellow soldiers, and Guinevere is a Pict (Keira Knightley). It deviates wildly from the traditional versions and at that time that was most welcome to me, as I’d read enough of the those. Zimmer would, once again, sign off on the score and it’s another mix of the bombastic with the ethereal. The female voice this time would be Moya Brennan’s (Clannad):

Skip Alexander and Troy, which are dreary, overly long and boring movies. Also skip Ridley Scott’s next epic, Robin Hood (2010) (with Russell Crowe and Cate Blanchett). I don’t remember much from it, except that it seemed to have some sort of “alternate take” on the traditional story (like King Arthur had) but was dreary and dull. After that Scott would try one more time to bring a historical epic to the big screen: 2014’s Exodus: Gods and Kings, a movie that had such a silly trailer and received such negative reviews that I didn’t even bother viewing it.

Instead, watch the two seasons of Rome (2005-2007), the lurid HBO/BBC collaboration with stellar cast and elaborate storylines. Or go back to its predecessor, 1976’s I, Claudius. It probably cost a fraction of Rome but its acting is still phenomenal, with Derek Jacobi and Brian BLESSED.

And in all this I’m not going into the older movies: Spartacus, Cleopatra, Quo Vadis and its ilk. The reasons for that are twofold: I’m not well-versed in those movies, and the few that I saw didn’t age particularly well.

I’ve briefly gone into other movies where you can admire Eva Green during my article on Casino Royale.

Orlando Bloom, in the meanwhile, seems like a likeable fellow but I don’t think anybody has ever accused him of having great acting skills. He’s OK as the foil Will Turner opposite Depp’s weirdo Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003) and its sequels. His casting as Legolas in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) and its sequels was well-done, but once again he’s the dull character that others can bounce off of. Maybe the best role for him was as a soul-searching yuppie in Elizabethtown (2005), a movie I’ve recommended before.

Closing out, I’d like to mention Edward Norton, who turns in a great understated performance as Baldwin of Jerusalem, the Leper King. He always wears a full-face mask, and yet he does more with his voice and body language than many actors could without wearing a mask. Go see him in movies such as American History X (1998), (as a reformed neo-nazi), the Fincher mind-trip Fight Club (1999) and the virtuoso Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014).